Before the first light spills across the savannah, a Maasai woman rises.

She moves quietly, purposefully the invisible web that holds her world together. In this, she is not alone; she is the heartbeat of countless homes across Africa. When the woman stirs, the household stirs.

If the fire is out, she bends low to stroke the embers. Soon, smoke curls into the crisp morning air as she prepares the first meal: sweet Kenyan tea, and perhaps bread or the last of the previous night’s ugali. This simple breakfast must fuel children for school, men for their day, and herself for the marathon of tasks ahead.

The cows announce her approach with low, impatient moos. They know their milker. As she sits to milk them, the ritual transcends sustenance. With few formal opportunities, Maasai women often sell this milk, turning a daily chore into vital shillings that buy food, pay labourers, and feed into community savings groups. She is not just feeding her family; she is fuelling the local economy.

Her work is a testament to resilience in the face of systemic absence. Where governments provide little social welfare, survival becomes a personal, daily innovation. For the Maasai, this innovation is tied to the land, relying on livestock breeds hardened by the sun and scarce rain. But climate change is rewriting the rules. Longer droughts, erratic rains, and dying animals erase years of wealth in a season. Yet, the woman gathers the pieces and begins again. Her endurance is the family’s lifeline.

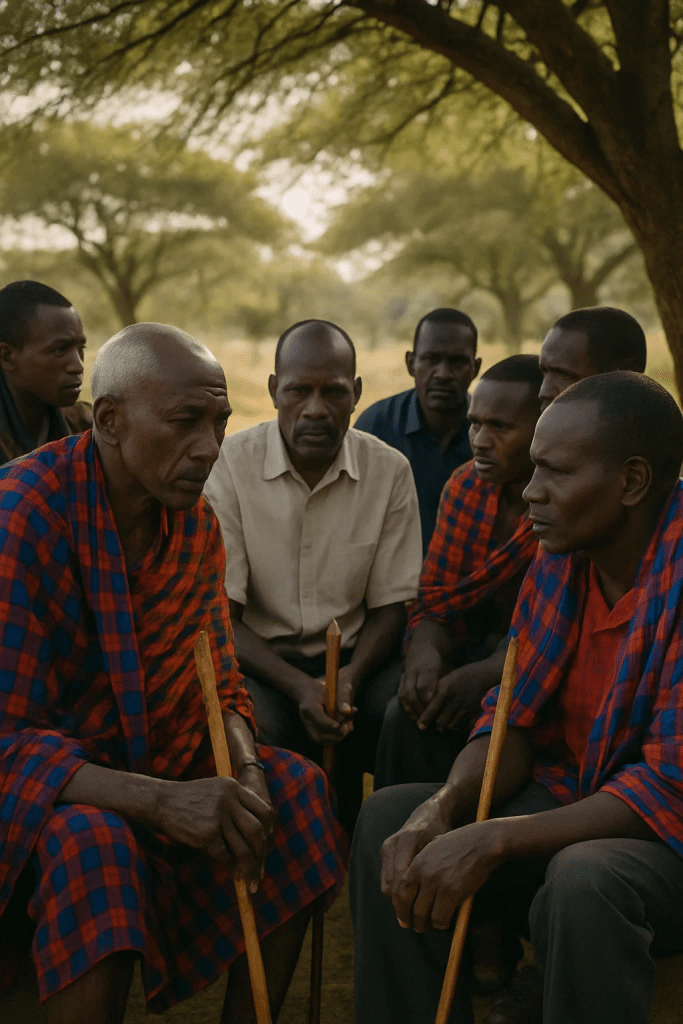

As men leave to debate politics in town, lamenting misused taxes, dreaming of elections, the women stay at home, holding the center of life. The reality in many African households is that the man may be the visible decision-maker, but his wife is the silent strategist, the gatherer, the planner. In some uniques cases, a woman with a voice is often seen as an anomaly but what if she was never built for small spaces? What if her voice is a sign of her survival against the system?

In the afternoons, under the generous shade of an acacia tree, you might find them. Groups of women, their hands threading intricate beads that carry both ancient patterns and modern economic hope. Their conversations dance between life lessons and community news, while children play at their feet in the dust. This is where culture is preserved and commerce is conducted, simultaneously.

Meanwhile, the rhythm of tradition continues: boys herd livestock, girls fetch water and firewood. Each role is mapped out, but the ultimate weight is the weaving of these threads into a coherent whole, falls upon the woman.

At the local town, her burdens are ghost stories in political halls. Men are summoned to meetings, their stomachs filled with promises and roasted meat, while the women whose labor sustains the very community remain unseen. Decisions are made without them, but they are the ones who inherit the consequences.

Still, she carries on.

She carries wood. She carries water. She carries children. She carries milk. She carries the invisible weight of survival and the visible hope of continuity. In doing so, she carries the future not just of her family, but of her community and her nation.

But her back is not unbreakable. Energy poverty, a changing climate, and systemic exclusion are heavy loads. The smoke from the fire shortens her breath. The hours spent searching for water steal her time. The livestock she depends on perish. And the policies designed to “save” her are drafted in rooms she will never enter.

When we talk about global progress, sustainability, or empowerment, we must first see her. We must remember the Maasai woman and the millions like her across the Global South. They are not passive victims waiting for a handout. They are survivalists, innovators, and the invisible architects of community.

This is not just a story.

It is a call to reimagine development by finally centering the women who have always carried the future on their backs.

Disclaimer: The images accompanying this story are AI-generated illustrations created using Sora. They are artistic interpretations intended to visually represent the themes and narratives described in the text, and do not depict specific real individuals or events.

Leave a comment