Introduction

I remember as a child when the rains did not come. The plains grew silent as wildlife and even birds migrated. The wind grew strong, whipping up dust that swirled like phantom tornadoes. The ground became bare, and the rivers dried up to cracked clay. My family owned livestock, and I saw in the eyes of our cows a profound sadness. I was told that drought and famine were a sign of God’s anger at the people for their sins. But as a child, I would ask silently, why should the cows suffer for the sins of human beings? I remember herds of cattle lining the highways, with young Maasai men forced to leave their families for unknown periods, migrating in search of rain.

We did not know the words “climate change.” We only knew the land was punishing us.

Today, the punishments have grown more severe, transforming from a struggle for survival into a catalyst for conflict. The same desperation that forced those migrations now fuels a different, more violent ritual. The cattle rustling I heard about as a child has evolved into deadly warfare. This was starkly demonstrated in the Baragoi Massacre of 2012, where at least 42 Kenyan police officers were ambushed and killed in the Suguta Valley, a place so brutal it’s nicknamed the “Valley of Death.” They were not deployed to fight terrorism, but to recover stolen livestock in a war over grazing land. In Northern Kenya, it is not uncommon to see a young pastoralist herding his family’s last few cows with an AK-47 slung over his shoulder. This is not a scene from a history book; it is the reality of the 21st century among pastoralist communities.

And my mind travels to the stories I heard about Sudan. I remember seeing tall, dignified, people with beautiful, melanin-rich skin and distinctive tribal marks and wondering who they were, only to come and find out that they are our neighbours from South Sudan seeking refuge in Kenya. The conflict in Darfur, which erupted over two decades ago, was often simplified as ethnic strife. But climate stress and expanding desertification deepened long-standing political marginalization, pitting communities against each other in a fight for survival over fertile land and dwindling water.

It is crucial to distinguish this from other conflicts. Africa has known wars inspired by greed where corporations and power-hungry elites destabilize regions for valuable minerals like coltan or diamonds, often funding militias to do their bidding. But the violence in Suguta, the instability in Darfur, and the crisis around Lake Chad reveal something different. They are conflicts where climate pressure collides with scarcity and insecurity. Not fought for profit, but for pasture. Not for control over mines, but for access to water.

From the Suguta Valley in Kenya to the vast expanses of Darfur, the same story is: Where the climate withers, conflict blooms.

COP 30, Brazil: A Pan-African Perspective

As global leaders prepare to convene at the COP 30 in Brazil, this is the story that must cut through the noise. These are not scattered local disputes. They form a continental pattern, shaped by a fast-changing climate that is dismantling the foundations of livelihoods, governance, and security across Africa. The competition for shrinking natural resources has become a spark that ignites violence, uproots communities, and erases hard-won development gains.

The old narrative of “tribal conflict” is no longer acceptable. It hides the real drivers. These crises are, in essence, climate-stressed resource conflicts. Africa contributes the least to global greenhouse gas emissions yet shoulders a growing share of the instability created by a warming world. If this imbalance is not addressed, the consequences will reverberate far beyond the continent’s borders with clear evidence in migration.

At COP 30, Africa’s demand must therefore be unmistakable: climate finance and adaptation strategies must be re-designed to treat peace and security as a non-negotiable pillar of climate resilience. This means direct investment in water access, climate-resilient pastoralism, mobility corridors for communities on the move, and conflict-early-warning systems. Supporting this is not a side project; it is the very essence of climate action. It is an investment in a stable future for all.

The Analytical Core: The Data of Scarcity

Across Africa’s drylands, climate stress is now measurable in disappearing lakes, shifting rainfall, and rising violence. Data shows a clear pattern: the less there is to survive on, the higher the likelihood of conflict (IPCC AR6, 2022). This is the anatomy of the climate-war nexus.

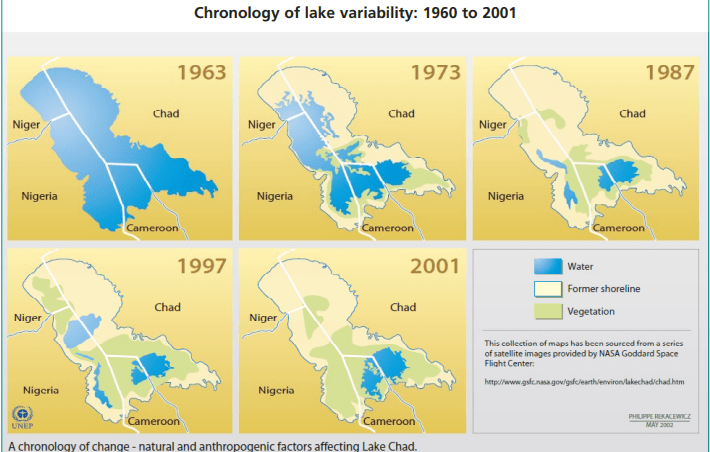

Lake Chad: A Case Study in Collapse

Lake Chad has shrunk by about 90% from its 1960’s extent, according to FAO and UNEP assessments (FAO 2011; UNEP, 2018). What was once a vast lifeline supporting farming, fishing, and pastoralism across four nations has retreated into scattered water pools, pushing millions into hunger and joblessness.

A World Bank analysis highlights how this ecological decline crippled local economies, leaving a vacuum that Boko Haram exploited where the state failed (World Bank, 2017). Security actors trace radicalization pathways directly to resource deprivation and displacement. Climate stress does not pull the trigger, but it loads the gun by destroying livelihoods, displacing populations, and eroding the social contracts that bind communities.

Kenya’s Pastoralist Belt: Conflict on a Drying Frontier

In Kenya, climate variability is systematically eroding an ancient system built on mobility and water access. Data from Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority (NDMA, 2023) shows:

- Severe drought now occurs every 2–3 years, instead of historically once a decade.

- Rising livestock mortality during prolonged dry seasons.

- Counties such as Turkana and Marsabit sustaining crisis-level food insecurity.

Academic research finds a direct relationship: decreased rainfall correlates with a statistically significant increase in violent incidents (Linke et al., 2018). Armed cattle raids, once seasonal and regulated by custom, now occur year-round. Young pastoralists carry firearms not for aggression, but to protect their families’ last remaining asset.

These communities are not violent by nature. Their economies are being dismantled by a climate that no longer supports pastoral life. This demonstrates a brutal truth: when livelihoods are lost, people fight for what remains.

Somalia: Drought as a Recruitment Engine

Somalia has faced five consecutive failed rainy seasons between 2020 and 2023, driving what the UN calls the worst drought in 40 years (UN OCHA, 2023). This has displaced over 1.7 million people due to climate-driven hunger and livestock collapse (UNHCR, 2023).

As communities lose everything, al-Shabaab fills the void. Security analysts document how the group provides food, loans, or livestock in exchange for allegiance and recruitment (International Crisis Group, 2022). Conflict intensity maps align almost exactly with regions most impacted by drought, revealing a stark correlation.

Sudan: Desertification and Displacement in Darfur

In Darfur, rainfall has declined steadily since the 1970s, while the Sahara expands southward several kilometres each year (UNEP, 2007). With about 75% of Darfur’s population dependent on rain-fed livelihoods, the consequences are catastrophic. As water points and fertile land vanish, longstanding tensions escalate into mass displacement.

Over 3 million people from Darfur remain internally displaced, with a UN Secretary-General’s report to the Security Council noting that environmental degradation and resource scarcity, exacerbated by climate change, continue to be ‘root causes of conflict’ in the region (UNSC, 2021).

Niger and Mali: The Sahel’s Violent Convergence

The Sahel epitomizes this convergence. Temperature rise here is 1.5 times faster than the global average (IPCC AR6, 2022). Pastoral routes collapse as farmland expands, and the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) records a sharp, sustained rise in farmer-herder clashes since 2011, particularly in Mali’s Mopti and Niger’s Tillabéri regions (ACLED, 2024).

Local disputes over grazing now merge seamlessly with jihadist insurgencies, turning resource competition into layered warfare. The result is the world’s fastest-growing displacement crisis (UNHCR, 2024), where climate pressure and insecurity fuse into a single, self-reinforcing cycle.

A Continental Pattern: The Anatomy of a Climate-Conflict Nexus

The crises spanning from Lake Chad to the Sahel are not isolated tragedies. They are manifestations of a single, devastating pattern repeating across the continent. When the ecosystem that supports life fails, the peace built upon it becomes fragile.

Climate change is rarely the sole cause of conflict, but it is the force that makes every other social, economic, and political stress more combustible.

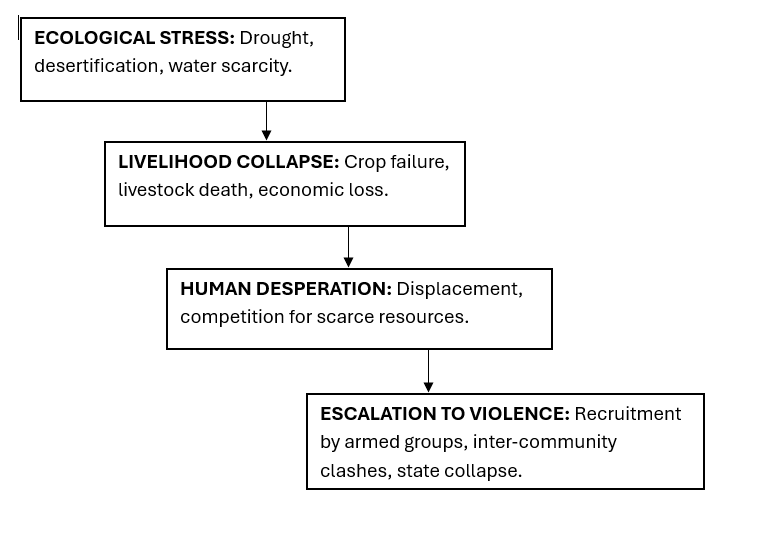

The process follows a predictable, vicious cycle:

Accelerants fuelling the cycle:

- Economic Loss → creates a pool of desperate, recruitable youth for militias.

- Forced Displacement → drives communities into contested lands, igniting new clashes.

- Weak Governance → enables armed actors to fill the void and rule by force.

- Eroded Social Trust → breaks down traditional conflict-resolution mechanisms, leading to endless retaliation.

This is the climate-war nexus in real time. It is not an abstract theory but a tangible reality where each drought, each failed crop, and each dried-up riverbed directly pushes societies closer to the brink.

The Human Cost: A Gendered Reality

While the climate-war nexus destabilizes regions, it systematically dismantles the lives of women and children with brutal precision. The collapse of ecosystems and security infrastructures places a disproportionate and gendered burden on them, exacerbating existing inequalities.

Increased Labor and Exposure to Violence: As water points dry up, women and girls are forced to traverse longer, more dangerous distances to fetch it. This increased mobility in volatile environments significantly elevates their risk of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). A study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2020) found a direct correlation between environmental degradation and a rise in SGBV, noting that resource scarcity is a key driver.

Deepened Food Insecurity and Health Crises: As primary caregivers, women bear the psychological and physical burden of feeding families amidst scarcity. When conflict disrupts supply chains and drought kills crops, they are the last to eat and the first to sacrifice. This leads to catastrophic malnutrition rates among children and soaring maternal mortality, as documented in UNOCHA’s (2023) humanitarian appeals for the Horn of Africa.

Loss of Social and Economic Security: When men are killed, displaced, or forced to join armed groups, women become sudden heads of household without the legal rights to land or livestock. Widowed by conflict and impoverished by climate, they are pushed into extreme vulnerability, losing social status and protection. The World Bank (2022) highlights that in fragile and conflict-affected states, women’s economic empowerment is critically hindered by these systemic shocks.

Therefore, the climate-war nexus is also a crisis of gender injustice. Understanding this is not optional for effective intervention; supporting women is not merely about aid but about rebuilding the very foundation of community resilience in the face of interconnected crises.

Conclusion

From the shores of Lake Chad to the pastoralist frontiers of Kenya and the crisis zones of the Sahel, the evidence is undeniable. Climate change is not a future threat but a present-day catalyst of instability, acting as a relentless threat multiplier in already vulnerable regions.

The old narratives of “tribal conflict” are not just inadequate; they are dangerous. They obscure the core driver: a changing climate is systematically dismantling livelihoods and security, creating a direct pipeline from resource scarcity to violence.

This reality demands a fundamental shift in how the international community approaches climate finance and adaptation. Supporting water security, climate-resilient pastoralism, and conflict-early-warning systems is not a side project in climate action, rather, it is its very essence.

As global leaders convene at forums like COP 30, the message must be clear: investing in Africa’s climate adaptation is not merely an act of environmental stewardship but the most critical investment possible in global peace and security. The climate war is already here. The choice is whether to fund the fight for peace.

References

Kenya (Conflict Events)

BBC News. (2012, November 12). Kenya police deaths in Samburu ambush rise to 42. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-20294747

Climate Science & Continental Frameworks

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. [Chapter 9: Africa].

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). (2024). Data export for Sahel region (2011-2024).

Lake Chad Basin

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2011). Lake Chad Basin: Climate Variability and Environmental Change.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2018). Lake Chad: Almost Disappeared.

- World Bank. (2017). Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. [Chapter on Lake Chad].

Kenya

- Kenya National Drought Management Authority (NDMA). (2023). Drought Early Warning Bulletins for Turkana, Marsabit, and Samburu counties.

- Linke, A. M., Witmer, F. D., O’Loughlin, J., McCabe, J. T., & Tir, J. (2018). Drought, local institutional contexts, and support for violence in Kenya. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(7), 1544–1578.

Somalia

- International Crisis Group (ICG). (2022). Averting an Famine in Somalia. Africa Report N°315.

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). (2023). Somalia Drought Response Situation Reports.

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2023). Global Report on Somalia.

Sudan / Darfur

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2007). Sudan: Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment.

- United Nations Security Council (UNSC). (2021). Report of the Secretary-General on the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur. S/2021/661. (Specifically, paragraph 34)

Sahel (Niger & Mali)

13. UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2024). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023.

Gender Dimensions

14. World Bank. (2022). Women, Business and the Law 2022.

15. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (2020). Gender-based Violence and Environment Linkages: The Violence of Inequality.

16. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). (2023). Humanitarian Needs Overview: Horn of Africa.

Leave a comment